January 15, 2008 (the date of publication in Russian)

Konstantin Cheremnykh

DIETER BODEN'S MOMENT OF TRUTH

German diplomat apprizes Europe of the reality behind the "young and fragile Georgian democracy"

DEVIATION FROM THE SCENARIO

DEVIATION FROM THE SCENARIO

Grand political players are traditionally superstitious: they dislike symbolical timing coincidences. The very democracy that was triumphantly born right at the moment of the US Presidential elections, in November 2004, started crumbling exactly on its three-year anniversary – and on the eve of the US primaries; thousands of people, crowding in Rustaveli Square, are now also encouraged with rebellious media – but these media are now directed against the once glorious winner of the "revolution of roses", while the "rosy" media are defamed as "the mouthpiece of dictatorship".

The White House failed to invent any tactical know-how for Columbia University postgraduate Mikhail Saakashvili except the traditional "nut-screwing" recipe. He had to get out of the mess on his own, grasping the chilled ironware of old symbols. Other ways of saving the "showcase of the Caucasus democracy", just fatally smeared with the exposure of machinations with the military budget, were of no avail. Thus, he found no other option but to voluntarily reduce his presidential term by one year on the highly symbolical day of November 7 (date of the communist revolution in 1917) and to schedule re-elections for the noon of the higher symbolical Orthodox Christmas, also timing the referendum on NATO membership to the discussion of necessity of snap elections of the Parliament – thus satisfying the opposition's demands.

An ostensibly broad democratic gesture, camouflaging violation of constitutional provisions, did not rescue his reputation. The first post-November 7 days resembled the revolutionist formula "railway stations-bridges-banks"; as the major resource of spreading rebellion is now mass media, the "rosy" leader started with a crackdown on disloyal media. This undertaking – surprisingly for him – aroused an outburst of long-accumulated irritation in the European community.

By that time, the European public opinion already underwent outside pressure over Georgia. In November, the German police was instructed to incarcerate the major troublemaker – ex-Defense Minister Irakly Okruashvili. The "beacon of Caucasus democracy" was supposed to be satisfied. But that was not enough: on December 28, major oppositionist candidate Badri Patarkatsishvili reported about a prepared assault on his life, and withdrew his Presidential bid. Days later, he unexpectedly returned to the race.

The next surprise was handed to the beacon’s patrons by the delegation of observers from the sympathetic Ukraine. The results of their exit poll were in favor of not Saakashvili but Levan Gachicheladze, endorsed by an alliance of oppositionist parties. The spectacular inconsistency with the official results questioned not only the reputation of the incumbent President but the myth of unity of post-Soviet "colored democracies". The whole scenario of the campaign, destined to add color to the tarnished Georgian roses, was falling apart.

BACK TO OLD FRIENDS

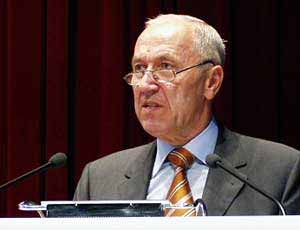

Something very unusual was happening at that time not only in Tbilisi, not only in Washington but in Europe as well. This was obvious from the fact that the statements of the most hated opponent of Saakashvili, named Badri, were taken serious. The selection of the candidature for the head of OSCE mission was even more exemplary. Formally, nobody could prevent Dieter Boden, chair of OSCE's Office for Democracy and Human Rights (ODIHR), from traveling to Georgia personally. But Boden was regarded as a figure in disgrace.

In February 2006, Dieter Boden was endorsed for the post of EU Special Representative in South Caucasus and Central Asia. However, his bid was blackballed, the high-level position being entrusted to Peter Semnebi, a Swedish diplomat with a much scarcer experience but a much higher loyalty to Washington. Ostensibly, the candidature of the 66-year-old Boden was rejected for considerations of age. But for some reason, the Brussels vote almost coincided with the decision of the UN General Assembly to skip the blueprint, known as "Boden's Plan", from the text of resolution on the Georgian-Abkhazian conflict. "Boden's Document" was suppressed in the same way as the 2003 blueprint on conciliation between Moldova and the unrecognized province of Transdniester, known as "Kozak's Plan" (after the name of Dmitry Kozak, then-Deputy Head of Russian President's Staff). In both cases, the handwriting of Washington's strategists of "surrogate warfare" was as plain as a pikestaff.

The German official with four decades of diplomatic experience was deprived of more than his brainchild. Actually, since the moment of Saakashvili's ascent to power in Tbilisi, the whole political and human network of mutual confidence he had been trying to establish on the unsteady and precarious soil of the Caucasus, had been demolished. "Boden's Document" – the only EU blueprint in which Abkhazia was recognized as a sovereign state (though in the framework of Georgia), was not the only result of his work in the region, in his earlier capacity of UN General Secretary's Special Representative. The major result as prevention of a large-scale military conflict which was looming over Georgia and the breakaway republic of Abkhazia in 2001-2002.

In early 2006, his contribution was actually recognized as needless. In late 2007, he was returning to the place, as he confessed, not only in order to carry out his OSCE mission but also in order to meet with his friends. Georgian politicians, with whom he had been acquainted for years, now found themselves on both sides of the barricade.

He was respected both in Tbilisi and in the unrecognized territories. "South Ossetia" newspaper, reflecting the official view of the other breakaway autonomy, appraised his assumption that provincial fascism still exists in Georgia. The Georgian military, in their turn, appraised the resoluteness Boden displayed when preventing a Russian convoy to enter Abkhazia in contradiction with the earlier signed agreements. He was respected as an experienced referee in professional sports – though he was never indifferent when dealing with an issue of principle.

It is noteworthy that Boden was perceived by in the region as not only an emissary of international institutions but also as a representative of Germany. Tamara Beruchashvili, deputy minister on European integration in the 2006 Government of Georgia, admitting after the failure of his EU mission's endorsement that "he performed too harsh and forthright on the Abkhazia issue", swiftly changed the subject, starting a talk about the significance of relations with Germany for her country. The lady obviously viewed Boden as a key figure in these relations.

FROM MUSEUMS TO TRENCHES

Dieter Boden's record of service was sufficiently long to take him seriously. His diplomatic career started in 1968 when most of the characters of the present Georgia's political scene yet attended the kindergarten. He spent to years in West Germany's Embassy in Moscow and five in the Consulate in Leningrad, later fulfilling various missions of the Foreign Ministry on NATO issues as well as on global control of armaments. In 1995-96, he worked in the independent Georgia as the head of OSCE's mission, later traveling to St. Petersburg in the capacity of General Consul.

He remembered the city well – and the city remembered him: primarily, not politicians but painters. In mid-1970s, he helped then-disgraced artist Pavel Kondratiev to evacuate his paintings to Europe. Years later, his art returned to the native country. Boden's name was familiar to specialists in literature: back in 1982, his book "The Image of a German in Russian and Soviet Literature" was published in Munich.

In his new old capacity, he became a favored guest in artistic and literary circles, organizing a unique exhibition entitled "Germans in St. Petersburg", staged in both countries and revealing half-forgotten episodes of history to both peoples. With a strange zeal of an intellectual, inconceivable for a bureaucratic mind, he studied Alexander Pushkin, and discovered earlier unknown Germanic motives in his poetry.

The insult from Brussels insult of 2006 was recouped with the gift, received from the new administration of St. Petersburg. The city highly appraised his personal contribution in reconstruction of the Amber Room of Catherine's Palace in Tsarskoye Selo: as an Ambassador, he had participated in the work of the Amber Room's international board of experts.

This was the same "harsh and forthright", "too professional" diplomat who demanded in winter 2000 to resume the Georgian-Abkhazian talks, and tasked his mission to establish control over the Kodor Hollow – right at the time when the gang of Chechen warlord Ruslan Gelayev was operating there. Two of his fellow citizens perished in a helicopter, downed by the warlords. The mission's officials were twice kidnapped. Still, he remained persistent in implementing his mission, and in separating the sides of the conflict, warning them from being provoked by criminal "third sides" – though emphasizing that the UN mission was fulfilling not more than a function of an intermediate.

His resoluteness, unexpected in an intellectual, irritated other Western players on the Georgian field. As a real professional, he did not buy primitive schemes in which evil intentions were always ascribed to Moscow. He tried to explain to Georgians that a war offensive is not a solution of an ethnic problem; he tried to convince the Abkhazians that formal independence is not a panacea for all the problems. Such diplomacy was not welcome among those who imposed a black-and-white picture of the world and the Caucasus.

Yury Vachnadze, head of the local office of Radio Liberty, referred to Boden with outspoken irritation. The German official intervened in the process of brainwashing Georgians in order to manipulate them into irrational and impotent self-perception of "eternal victims". He proposed solutions which could be implemented by the local peoples independently, without looking back at the Washington "cradle of democracy". He demonstrated with his behavior that the West is represented not only with the view of the White House; that formal democracy is not an only achievement of Western culture. The unvoiced irritation of the vicars of Pax Americana was helpless – as in order to reassure him, they required argumentation on a similar level of competence.

THE CRUMPLED PEACE-BUILDING

Actually, Boden's words and deeds far exceeded the framework of mediation. In 2001, a journalist from Sukhumi, Abkhazia, inquired him on the issue of Meskheti Turks, who fled from Georgia in early 1990s when President Zviad Gamsakhurdia raised the motto "Georgia for Georgians!". Boden firmly stated that replied that the Georgian side will have to retrieve the Meskheti refugees, or bear responsibility before the Council of Europe. He thus addressed an inconvenient issue of ethnic and cultural rights which Gerogia's patrons, flirting with President Eduard Shevardnadze and looking for a substitute behind his back, tried to sweep under the carpet.

On April 2, 2002, Dieter Boden convinced Tbilisi to withdraw its troops from the Kodor Hollow. This decision was made in an unusual format, involving – in an equal status – official representatives of Georgia, top officials of Abkhazia, the UN mission, and the Russian peacekeeping contingent under the command of Major General Alexander Yevteyev. In his efforts of disarmament of the area, adjacent to a yet instable Chechnya, he cooperated with Abkhazia's Prime Minister Henri Jerghenia and Georgia's State Minister Avtandil Jorbenadze – the person whom Shevardnadze viewed as the successor of his own.

Months later, on the eve of his departure from the region, Boden performed one more, most impressing and desperate diplomatic mission. He conveyed Shevardnadze's proposal to take charge for the Georgian-Abkhazian negotiations to Aslan Abashidze, leader of the semi-loyal Adjarian autonomy. In November 2002, Abashidze, a political rival and personal opponent of Shevardnadze, agreed to accept the post of Georgian President's special representative in the Tbilisi-Sukhumi peace talks.

Abashidze's Alliance for Democratic Revival Party was then the only political force with influence both in Georgia and the breakaway autonomies. In August 1992, he unsuccessfully tried to prevent Shevardnadze from military intervention into Abkhazia, this fact being remembered from both sides of the borderline by the war-weary population. Addressing the President, Abashidze then proposed: to suspend economic embargo from Abkhazia; to open railroad, highway, air and marine transport lines; to restore the Inguri Hydro Power Plant, to allow transit of gas and electric energy to Turkey across Abkhazia, the Georgian provinces of Samegrelo and Guria, and Adjaria, for the benefit of the whole Georgia's national income.

This project of a peaceful confederation, which could be headed solely by Aslan Abashidze, was discussed with involvement of Dieter Boden. His name could be found in the exceptionally accurate and unusually truthful volume "Russian-Georgian Dialogue", edited by Sergey Kortunov and Sergey Oznobishchev, where a Georgian and Abkhazian reader could find proof of criminal involvement in the 1992 Georgian-Abkhazian war – as well as a similarly clear conclusion that the State Dept is uninterested in peace in this region. The collected volume was a result of a joint effort of the Moscow Institute of Strategic Assessments and Friedrich Ebert Foundation – an institution of the Social Democratic Party of Germany that Boden was a member of, spending a while in SPD's Bundestag faction.

Abashidze's project was ruined right after the arrival of top managers of Gazprom and United Energy Systems. Right after that, Speaker Nino Burjanadze unleashed an ugly speculative scandal over Georgia's energy dependence from Moscow. The pseudo-left rhetoric of the "revolution of roses" started unfolding in accordance with the scenario implemented in 1999 in Belgrade. The longtime efforts of Boden's subtle popular diplomacy were thrown aside and crumpled with a wave of a well-staged public rage.

The young generation, lacking experience, responsibility and understanding of what had happened with the land of their own, ranted anti-corruption slogans, kicking out "the old men" – and making clear from the beginning that Abashidze was going to become one of the primary targets of the "rosy revolt", while the tiny but prosperous autonomy of Adjaria – to be merged into the Soros-designed "new Georgian economy".

Dieter Boden, chair of the OSCE delegation in Georgia, raised his concerns exactly over ballot-rigging in Adjaria, where disappointment with the incumbent power of Tbilisi naturally reached the highest point.

THE FUTURE ECHO OF THE PRESENT CHALLENGE

Many recommendations of Kortunov's book now sound naive. The power lines have since shifted along with political reasons; Abhazia serves now a new role in Europe in the context of the Kosovo problem, created by Washington on its own political and shadowy economic considerations.

Boden's logic may be accepted or not. Still, it is impossible to overlook its core motive of reconciliation which Boden pursued in the region, contrary to the conjuncture and the views of the high and mighties. Only today it is becoming obvious that he managed to reach significant results not only in the area where he had been dispatched but at home as well.

On January 5, the election commission declared Saakashvili the winner of the Georgian Presidential race. On January 7, Berliner Zeitung’s report put this victory under great doubt. That was just a preface for a devastating article of Florian Hassel in Frankfurter Allgemeine, built on the evidence of Dieter Boden, chair of OSCE mission in Georgia. The Western audience was now informed firsthand about "gross, arbitrary and deliberate violations of the ballot, partly registered by the Mission", and the "atmosphere of chaos in the Georgian election authority".

Maybe for the first time, the chair of OSCE's mission, as well as the chair of ODIHR, expressed a view completely contradicting to Washington's assessment. This viewpoint, actually made public already on the day of elections, contrasted also with the ritual affirmation of Anne-Marie Isler-Beguin, chair of Europarliament's mission, who interpreted the results of elections as "one more step forward on the pathway of a young and fragile Georgian democracy".

Dieter Boden's remarks could be hardly viewed as just score-setting with the fainthearted bureaucracy that had deliberately and unscrupulously nullified the results of his professional work. That was more. He ventured an outright expression of disaccord with the US tactics of surrogate warfare and "colored" revolts which had ripened in European political circles years before. Now, the enlightened European public will develop a different view on Georgia's reality, affecting the assessment of the oncoming parliamentary elections.

This untimely revelation will hardly be forgiven to the German diplomat. His opponents are likely to try to expose him as well, digging in the St. Petersburg period of his biography and searching for connections to be interpreted as doubtful and ominous. He is going to be declared a persona non grata in the official Washington. However, his behavior in Georgia may become a precedent for other cases across the globe where high political strategies are intertwined with powerful criminal interests, dooming the local population for longtime disasters – from Kashmir to Iraq, from Liberia to Kenya, along the whole "arc of instability" – and marionettes with American diplomas, losing the gloss of "knights of democracy", will appear before the world community in their proverbial futility of naked kings.

Number of shows: 1785

ENG

ENG

ENG

ENG