16.06.2008

June 11, 2008 (the date of publication in Russian)

Alexander Rublev

FROM BISMARCK TO GORBACHOV

Former Russia's Ambassador in Bonn urges "to be cautious" with Germany

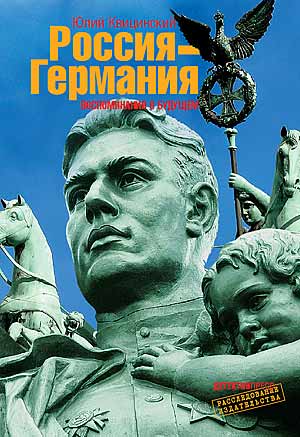

On June 10, REGNUM news agency presented a new book "Russia-Germany. Reminiscences of Future", authored by diplomat Yuliy Kvitsinsky and issued by Detective-Press Publishing House. In this book the author expresses some highly controversial ideas and comes to very surprising – or even "shocking" Ц conclusions.

On June 10, REGNUM news agency presented a new book "Russia-Germany. Reminiscences of Future", authored by diplomat Yuliy Kvitsinsky and issued by Detective-Press Publishing House. In this book the author expresses some highly controversial ideas and comes to very surprising – or even "shocking" Ц conclusions.

With his longtime diplomatic record, starting from a job of a junior interpreter and rising to the post of USSR’s Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, Yuliy Kvitsinsky is held in high esteem in diplomatic circles. During 18 years, he worked in Germany, and was closely acquainted with top politicians of FRG and GDR. In 1986-90, he headed the Russian Embassy in Bonn. Later, he spent several years as Russia's Ambassador in Norway. In 2007, he was elected to the State Duma from the list of the Communist Party, and presently is in the position of Deputy Chairman of the Duma's Foreign Policy Committee.

Looking back at the experience of Russian-German relations from Bismarck until today, the author indicates that the same developments may be interpreted from two angles. In the first case, the line is drawn from one positive episode to another, regarding the rest as unfortunate flaws. In the second case, lines connect black pages of the history of bilateral relations, while the rest is considered as an exception. Kvitsinsky does not identify himself with the latter approach but warns that the former is equally inadequate.

Kvitsinsky's warnings sound unusual. At the time when Germany is broadly viewed as a special European partner of Russia, he urges diplomats "not to flatter themselves with the love affair with Germany", so that "not to repeat Gorbachov's mistakes". He refers to the failed expectations of the former General Secretary that dismantling of the Warsaw Pact and the fall of the Berlin Wall would be followed with dismantling of NATO and not its further expansion.

"In fact, an alliance with the United States and conservation of NATO, although with corrections, are the principal cornerstones of Germany's policy", insists Kvitsinsky. "Germany should not be idealized, as well as demonized. Germans always do what they consider expedient in the particular situation. Why should we expect from them romantic selflessness for the sake of Russia? After all, we don't expect that from other countries".

Being skeptical about Russian-German strategic partnership and calling it a "romantic myth", Kvitsinsky analyses the period between the times of Otto von Bismarck and Russian tsars, and of Gorbachov and Kohl, and describes the same "algorithm": in the period when Germany needs assistance from Russia, German politicians talk with us in a language of values and ideas; however, as soon as they receive what they want, the "high style" is replaced with cynical calculation. "Twice, in 1871 and in 1990, Russia said "yes" to Germany's unification, but Moscow's expectations of German historical gratitude never came true Ц quite the opposite. Bismarck refused to support Russia at the Berlin Congress; meanwhile, the Kaiser unleashed a war, later known as World War I", the diplomat explains.

One hundred years later, Germany pursues a similar policy, believes Kvitsinsky. "Germany continues to press Russia out of its traditional spheres of influence in the post-Soviet area. Germany's ruling circles "have grasped everything they could during the division of the Soviet pie Ц in the Baltic, in Ukraine, in the Caucasus, in Central Asia, using the label of either EU or NATO as a guise".

In Kvitsinsky's view, the only difference between approaches to Russia from Kaiser's Germany and today's Federal Republic is that a century ago, German elites undertook an independent offensive in the Russian direction, and today, they are ready to perform as a part of an international "shareholder team". The dominant stance in German mass media, Kvitsinsky says, leaves no doubt that "public opinion" is being prepared for such a perspective. Warning against unilateral concessions to Germany, the author emphasizes that the current rapprochement between Moscow and Berlin should not represent "a one-way street".

Summarizing his message, Yuly Kvitsinsky concluded his book with a number of recommendations for diplomats working in the German direction. This advice is not necessarily going to be followed by the younger generation of Russian diplomats, but Kvitsinsky's authority suggests they should be taken seriously.

1. Russia, the USSR, and the present Russian Federation Ц with certain historical nuances and deviations Ц regards relations with Germany as a major direction of foreign policy. This is reasonable. However, declaring this priority, Russians try again and again to win a special favor of Germany, expecting gratitude, faithfulness and love from the partner. But Germany is a priority for many other countries, primarily the neighbors. Germans are quite aware of their possibility to choose a bride and change her for another when this is considered expedient. This manner may be influenced only with self-confidence and firmness of the partner.

2. Since the times of Bismarck, Germany's preferred partner was Britain (now the US). Partnership with Russia is an additional option that is made only when the former option does not work, and usually serves for the purpose of pressure upon the Anglo-Saxons. This approach enables Germany to perform as the pacemaker in Russian-German relations. In any case, a love affair with Germany suggests not more than a "marriage of convenience", implying conditions that provide Russia sufficient freedom of maneuver along with a possibility of strong influence on the partner.

3. Dramatic U-turns in Russian-German relations are usually performed by conservative political circles. For German social-democrats and liberals, abrupt positive or negative shifts in foreign policy approach are less typical. Mutual understanding can be reached with both sides of the political spectrum, but in critical situations, it is easier to deal with the conservatives Ц though with caution.

4. Hopes for Germany's transformation into a self-sufficient pole in global policy, even in combination with other EU nations, are premature. At present, Germany is not ready to venture tensions with the United States and other NATO countries over excessive rapprochement with Russia; besides, this is not so far considered necessary.

5. Some other European nations, fearing increase of Germany's strength, try to canalize this rising potential to the east and south-east of Europe, as they usually did in the past. Now the Western unity is based on mutual forcing Russia back to the East and on opening Russia's mineral wealth for joint development and exploitation by the West. Meanwhile, German corporate interests in the East, especially in natural resources of Russia, don't contradict with other Western interests, and there are no grounds to expects serious conflicts among Western powers in this issue.

6. Germany's eastern policy significantly depends on Russia's strength or weakness. There are no grounds to expect changes in this regularity. Thus, the solution of problems in Russian-German relations should be started from Russian domestic problems.

Number of shows: 2148

rating:

3.3

ENG

ENG

ENG

ENG