January 15, 2007 (the date of publication in Russian)

Konstantin Cheremnykh

BEYOND FUEL SWAGGER

Not everything in this world is measured in dollars per cubic meter

On the eve of the Old Style New Year, Russian federal TV channels were not going to confuse the audience with complicated problems. Any problem was presented in a most consumable version. Here are the generous Russians, there are the ungrateful Byelorussians. We kindly provide them gas for the lowest price, and they nastily impose transit duties.

On the eve of the Old Style New Year, Russian federal TV channels were not going to confuse the audience with complicated problems. Any problem was presented in a most consumable version. Here are the generous Russians, there are the ungrateful Byelorussians. We kindly provide them gas for the lowest price, and they nastily impose transit duties.

The TV air seemed to be prepared for not just ignorant but for illiterate audience. Actually, when Gazprom established its export prices for CIS states in 2005, the price for Minsk comprised $45 per cubic meter. Today's "lowest" price, now called "privileged", exceeds the original one more that twice. As the state-run TV electronic media were explaining to the audience, yet giddy from Christmas hangover, this double increase was justified, as the insidious Byelorussians have been cynically re-selling Russian oil products (not natural gas, but gasoline, produced from Russian crude oil on Byelorussian, but Russia-owned facilities). Therefore, the Russian Government (this is reported in a sputter) introduced, days before the New Year, NOT ONLY a double price for gas, but also a $180 per ton tariff for oil, delivered to Belarus. And already after that, Minsk, in its turn, imposed the "cynical" 45 per ton customs duty.

Surprisingly, the referred re-export operations appeared to have been conveniently practiced since 1998, i.e. since the time of a careless Boris Yeltsin, who allowed Minsk to pull out from an earlier signed agreement – officially cancelled in 2001, i.e. under Vladimir Putin.

In its turn, the Byelorussian side reminds – as you can learn exceptionally from Belarus TV Ц about three different agreements unilaterally broken by Russia, on the contrary to the general customs agreement, signed in the framework of the CIS Customs Alliance.

Most curious, however, is the fact that all those contradictions had never been made public for the past nine years. Minsk hadn't been grilled for the notorious re-export – as well as those Russian oil corporations, apparently involved in the illegitimate (or undesirable) practice.

And even when the issue reached TV air on the background of the inter-government bargain, these oil corporations, namely Surgutneftegaz and Rosneft, were "unavailable for comment" when Vedomosti, the major business daily, addressed them on January 12. From this paper's research, however, it may be logically concluded that the revised conditions of oil export to Belarus, eventually approved by Prime Ministers Mikhail Fradkov and Sergey Sidorsky (that Belarus lifts its duties, while Russia's tariff is reduced from 180 to 53, but only for the amount of oil used by Minsk for its industrial needs, not a ton more), is most unfavorable for an intermediate company, named Sunimex ("sun-" is apparently Surgutneftegaz). Since this moment, this intermediate company is unable to capitalize from the "super-normative" oil, and its general director, a little-known Mr. Kishilov, won't be able to allocate himself a bonus for the next Christmas' trip to Courchevel.

From all this, a really curious and educated reader (who learns about major economic events not only from TV, and is able to read the lengthy Vedomosti's research to the end), may eventually conclude that the wrongdoings, ascribed to Minsk, actually involve a narrow but witty circle of Russian wheeler-dealers, for whom the special status of Russia-Byelorussia partnership had been serving for nine years as a convenient guise for formidable incomes. Still, Alexander Lukashenko is used as a whipping boy, while the "invisible men" from Sunimex are not focused upon – until some French or German policeman, by occasion, inquires them on the origin of their visibly enormous fortunes.

THE COURCHEVEL BACKGROUND OF THE "BELORUSSIAN CRISIS"

Sincerely speaking, my feelings – as well as, I guess, those of a very broad Russian audience Ц were rather controversial, when right after the report of Belorussia's "insidious" capitalization from Russian transit, I heard from Russian TV that Ц hooray! Ц Mikhail Prokhorov, president of Norilsk Nickel, is released from custody by French prosecutors in Courchevel, "as well as the rest of the Russians".

It was certainly clear that the unusually excited French reporter of Russia TV did not mean the whole Russian population, including this author and the personnel of Norilsk Nickel, but only those particular representatives of the "top cream" of Russian society who can afford a New Year trip to the most luxurious French resort. It was unclear why the whole of the audience should share this delight.

After that, Russia TV's audience was supposed to get excited over one more achievement of Russia – namely, over the amendments to the Russian federal legislation toughening prevention of infringing merchandise. The TV report featured a lady, raising an innocent question during the discussion in the State Duma: why does the Parliament have to hurry to satisfy grudges from foreign producers if most of the Russian consumers can't afford relevant licensed articles? A resolute member of United Russia Party explained, in a didactic tone, that illegal copying (of textile, perfume, or software) is as criminal as, say, stealing a sausage from a supermarket. "This sausage might be stolen by a poor person", he admitted. "But that is a different issue".

Right at that time, in the culmination of the Russia-Belarus trade debate, the Russian Government was composing a list of Byelorussian goods now subject to import tariffs. What imported production is going to replace these goods – cheap textiles and agricultural machinery, among other categories not manufactured in Russia since the degradation of formerly state-run industry during Gaidar's reforms Ц was left unexplained. Probably that was also a "different issue".

On January 13, the federal TV channel eventually made clear that the Russia-Belarus debate involved not only gas and oil products but a number of major non-fuel matters. Particularly, the Belarus-produced sugar which also underwent duties along with oil days before Christmas.

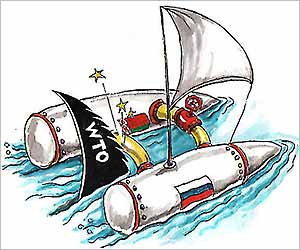

Meanwhile, Izvestia's arithmetically talented but not much informed liberal observer delivered a conclusion that the reduction of the oil export tariff from $180 to $53 means that Putin has conceded to Lukashenko. This seditious suggestion was immediately rebutted by Russia TV, which revealed that in the process of bargain, Minsk agreed, in exchange for the mentioned reduction of the fresh-imposed tariff, to lift earlier introduced limitations for dozens of Russian goods, imported into Belarus. Thus, Russia TV continued, the Belarus side is fulfilling – guess what? Ц conditions imposed by WTO.

Better late than never, we are told which three letters comprise the true matter of the debate.

To be frank, just before Christmas, Russia TV did mention WTO conditions, admitting that by increasing export gas price for all the CIS countries (regardless from their political relations with Moscow), Russia fulfils EU's conditions for Russia's entry in the World Trade Organization.

But this fact was mentioned only once and in half-word. What Russia TV was much more eloquent about was that Moscow's contradictions with Minsk don't imply any contradictions between the two friendly peoples. Which suggested that in the place of Alexander Lukashenko, some other, more convenient person, would have okayed all the newly-introduced terms with no objections, despite dire effects on his national economy – as some other CIS leaders did. That is quite true. To tell the whole truth, however, we have to add that Russia's entry in WTO is also rather a blue dream of particular members of the Russian government than expression of the will and benefit of the Russian people.

As we were explained, the Russia-Belarus debate has only contributed to the anti-integrationist arguments in Minsk, for the benefit of Lukashenko, as the local opposition just can't help sharing his rhetoric vis-à-vis Moscow. Now, in case of economic difficulties in his country, Lukashenko has received a convenient opportunity to point at Moscow. True, again. But it's equally true that in case numerous Russians – and whole sectors of the Russian economy Ц face economic problems after the entry in WTO, Moscow would be able to blame nobody but itself.

The only explanation we are supposed to get for the advantages of WTO membership from federal state-run media is that all the developed countries are already there. That is again true. Equally true is the fact that neither the US nor German economy today belongs to itself. This achievement of globalization, however, is not appreciated by a number of defiant nations, particularly Belarus. For this reluctance, Lukashenko's regime is faced with political sanctions from the United States. These sanctions are highlighted by the Russian state-run TV channel as joyfully as the report about Russian producers who, at last, are able to export as much to Minsk as they can.

FOREIGN "DOMESTIC" PRODUCERS

What producers have acquired benefits from the concessions made by Minsk as a result of Moscow's oil-and-gas extortion? In the first line of this list, we see the glorious beer industry. Curiously, this most successful branch of Russian non-fuel production is the least Russian-owned. The famous Siberian Crown beer, massively advertised in "old Russian" style, is a product of a 100% Irish-owned brewery.

The manufacturer of Baltika, "conquering the whole globe" (according to its ads) and being really the first largest donor of the St. Petersburg city budget, is 80% owned by the Danish-Finnish Baltic Breweries Holding. The dominating ownership rights allowed this company, two years ago, to kick out its general director Taimuraz Bolloyev, with no regard for his honor of a toastmaster at President Vladimir Putin's birthday parties. Similarly, the thin minority of Russian shareholders is now unable to prevent the sale of the whole successful business to Anheuser Busch, the leading US beer corporation.

Therefore, the compromise, unwillingly made by the Government of Belarus, is playing in the hands of grateful third sides. Similarly, import duties for Byelorussian exports would not benefit not Russian producers of trucks – as they are less competitive at the global market than Byelorussia's MAZ and BelAZ Ц but John Deer and Caterpillar.

The Mogilev Elevator Plant, in the times of the USSR, produced 80% of the domestic and industrial elevators used in Leningrad. Fifteen years later, the newly-revived Russia has got – better late than never Ц focused on the living conditions of its citizens. The relevant program (even more, a national priority project) is entitled "Affordable Housing". The project contains a number of directions, but its real physical element is a house, and an indispensable physical element of a house is an elevator. How will this ambitious project coexist with Russia's entry in WTO, if on the next day, Moscow will be forced to purchase, necessarily, not the affordable Mogilev production but the much more expensive OTIS? Will that bring us closer to the shining horizons of cheap housing market? Could arithmetically educated specialists from the Economy & Trade Ministry start the relevant calculations today, not tomorrow? Could they also calculate the benefits of Anheuser-Bush from the access to the Byelorussian market, received from Moscow as a present?

In their turn, those US producers which are so adamant in criticism of piratic merchandise could be asked: dear sirs, where were you in year 1991? What have you been waiting for? Maybe, for a stable and presently solvent demand for licensed products, achieved – with no expenses for advertising Ц due to dissemination of the notorious piratic stuff? If that is true, why not to calculate the losses of the domestic competitors? If we start calculating, let us calculate everything.

HOW MUCH IS THE LOSS OF THE FACE?

According to a Russian proverb, what is good for a Russian is mortal for a German. While the Russian audience was enjoying New Year's TV festivity humor, the consumers of Russian fuel were hardly in a holiday mood. Their feelings at the moment could be guessed with a high probability. A year before, Europe was faced with a similar scandal over Ukraine. At that time, the response varied in a range from amazement to compassions with the poor Kiev. When the same happens for the second time, a normal response of a healthy psyche is the affect of irritation. Generally, irritation is a response to reiteration. It is an active emotional state; it suggests an impetus for undertaking some measures. Relevant measures are supposed to get rid of the irritating factor, namely, from the inability of Russia to solve problems with its own closest neighbors, even those associated with special Union agreements. And therefore, to seek other options for fuel imports.

Right on the peak of the Moscow-Minsk brawl, one of those alternative routes of import became an object of serious discussion. Namely, that was import of Azeri gas to Europe via Turkey. This transit route is not approved by the US Congress, where the Armenian lobby has now gained strength. However, Baku and even the super-loyal Tbilisi are ready to "act with no regard to ANY (as Ilham Aliyev said) United States". Probably not only from excessive own courage but also from the fact that Turkey not always looks back at the US dictates today.

Last autumn, Russian TV reporters were much excited with the fact that the United States today can't allow itself a direct support of a war potentially waged by Georgia against its breakaway territories. However, for the same reasons, the United States is not more able to dictate foreign policy to Ankara. Which, in its turn, would like to use the lever of EU's dependence from its deliveries to facilitate its long-expected acceptance to the European community.

Search of circumventing routes is a normal response to an inadequate behavior of the major supplier. While reliability of a business partner can be arithmetically measured, reputation is a less calculable, non-linear notion. A loss of face is internationally regarded by physicians as an injury as serious as a fracture of the bearing extremity, and is even less curable. From the viewpoint of state interests, the Courchevel flaneurs should face an impressive multidigit bill for the damage for the state's reputation, instead of stupid attempts to fence them off. .

WHAT WE OWE TO MINSK

I don't know in which school Gazprom's PR specialists were educated; surely, that was not the school of Russian theatre classic Stanislavsky who measured the success of a play with the audience's belief to the actors. The Christmas fuel drama with Lukashenko starring as Mr. Thief was not taken seriously by the international audience. The Inopressa website failed to enrich its collection of foreign-published articles under the subtitle "Putin Is Young And Strong". A year ago, Russia was grilled by Western place for "arrogance". This time, many observers intoned that "Russia is scared", "What the eyes fear, the hands do” It is too well known that Moscow depends on Minsk in military strategic affairs.

Still, radars and ABM are not the only benefit obliging Russia to Belarus. Any observer with a non-injured memory would admit that with Lukashenko's election victory in 1994, the Anglo-US design of an oil transit corridor circumventing Russia, a key element of Zbigniew Brzezinski's design of a "sanitary cordon", was doomed. Therefore, Russia's oil and gas-producing community owes to Lukashenko more than anybody else.

Such kinds of geopolitical service are paid, and this is practiced by all nations. Among WTO members, this is especially typical for the United States, which invests millions of dollars in close and remote, democratic and dictatorial, enlightened and primeval regimes across the globe, paying for implementations of the US foreign policy tasks. The monetary return of those investments may be tiny or even negative. Still, these investments pay back with strategic advantages for the superpower. Not everything in global policy is calculated in market terms. The referred Brzezinski corridor was based more on geopolitical than monetary calculations.

Non-market considerations, in their turn, are not restricted to strategic assessments. Such non-material categories as common historical memory and military fraternity also belong to the range of "invisible currencies". The recent coup d'etat in Thailand was successful not only due to Lockheed Martin's involvement in the campaign against Prime Minister Shinawatra but due to the long-time memory of the US cooperation with the Thai military in the Vietnam campaign.

Gratefulness is not measured in US dollars per cubic meter. Still, its absence is experienced as lack of fresh air. This feeling is familiar not only to Belarus ministers but to the Byelorussian people as well. When Russia's Finance Ministry reports about its comptrollers dispatched to Belarus' western border, I just try to remember how those officials in Brest will look in the eyes of Byelorussian border servicemen, as well as their Russian comrades-in-arms from the still existing CIS Defense Treaty forces.

My concern is not about the Byelorussians. To my mind, they are luckier than many other former Soviet peoples. Today, Byelorussians are politically protected not only by Lukashenko but by a whole array of states – Arabic, South Asiatic and Ibero-American. While the Belorussian envoy was using a small private flat as an office, as well as the place of residence Ц as, in his status of a representative of a "union state", he was not granted a full-fledged diplomatic status, while thousands of idle officials assembled in inactive and meaningless "union bodies", the world around was changing. In the new different world, Belarus found itself on a different planet of anti-globalist states. The major feature, making Belarus common with this newly emerged archipelago of states is that the Byelorussian nation is not divided in itself.

Meanwhile, the Russian nation is divided. An immense distance separates Mikhail Prokhorov from a worker of the Norilsk Plant, and a Finance Ministry official from a Russian Army's draftee. This astronomic distance is Russia's Achilles heel. Not the only one. The statistics of general economic progress, including GDP, does not consider the huge difference in incomes of Russian citizens. It equally disregards the structure of economy. What is really precious for Russia in partnership with Belarus is the possibility to cheaply acquire technological knowledge in the spheres abandoned in Russia but kept alive in Byelorussia's "unnatural" reserve. This is one more pretext for an at least careful attitude to the neighbor, regarding also its contribution in Russian non-fuel production cycles.

DO WE NEED ALLIES?

Now, let’s address to the issues we are usually reluctant to dwell upon. First, that the prices for oil and gas are not everlasting. Secondly, the expectations that an incessant war in the Middle East would help us to keep those prices high for a long time, is at least immoral. Thirdly, the non-market categories of morality, after a substantial period of time, are again of demand, and even at the US Congress – as the world is changing not in favor of the presently reigning financial globalism. In this changing world, not only financial stocks of major US corporations are being devaluated. In the same Latin America, long-time ownership of earlier dominating corporations is being nationalized, with no public rallies of liberal democrats seen to protect their interests. Who guarantees that in a while of a decade, a similar anti-globalist partnership of nations does not emerge also in Eastern Europe?

During the last year, the first bells of such a possibility already rang. The state-run Russia V channel responded with a presumptuous list of countries, dependent on Russian oil supply. Meanwhile, some East European states possess not only their own oil and gas but also the presently inactive nuclear energy facilities, their functioning prevented today only by the Brussels bureaucracy's environmentalist obsessions. Russia's policy in Eastern and South-Eastern Europe is today practically restricted to corporative expansion. Meanwhile, we are associated with those nations not only with the notorious pipe but also with the heritage of cultural and military history. Not only gas and canned peas associated Russia and Bulgaria but also the Mount of Shipka. Neglecting this powerful non-material asset of partnership, we cut off the ties along the whole perimeter of Russia.

Again, Russia owes its economic success not only to its own potential but also to weakness of other nations, which in many cases is just temporary. From the abovementioned Turkish-Azeri agreements, it is visible that the weakness of the US superpower cleans the space of influence for regional powers and their alliances. Similarly, the crisis of the "American dream" gives birth to a whole series of anti-globalist initiatives. The disintegration of the once solid community of Western powers should serve for Russia as an impetus for seeking new allies rather than for banal corporate swagger. The maladies of the society are elevating the importance of this task – as well as the extent to which the machine of state propaganda is infected with corporate conceit, blocking any feedback with this society.

This neglect of feedback has once already played a bad trick with most talented Russian leaders. In the times of Emperor Alexander III, the ruling class had an impression that the nation does not need allies beyond its Army and its Navy. Meanwhile, the lower class was abiding in the condition, described by satirist Saltykov-Scedrin, in his pamphlet "The Land of Abroad", in the image of a "boy without trousers". Decades later, this boy grew up into a revolutionary proletarian.

The excesses of the Courchevel fops, accompanied by a compassionate chorus of state- and private-run media, are a slap in the face of millions of today's Russian "boys without trousers", well informed of the wealth of their nations and thus twice humiliated. This slap in the face is twice more painful when the current Tsar is not doing what the founder of St. Petersburg would do with these guys – not giving them a sound whipping.

WHO NEEDS A PUTIN-LUKASHENKO QUARREL?

The new debate between Moscow and Minsk provided not Gazprom and Transneft with most substantial dividends but rather the professionals in the art of discrediting Russia and its leadership. Not for the first time, trained scoffers recognized the origin of the Moscow-Minsk conflict not in financial and generally economic difference in views but in a non-material factor of personal mistrust between Vladimir Putin and Alexandr Lukashenko. Not accidentally, the recent poll of Echo of Moscow Radio, featuring a thrice more popularity of Lukashenko in Russian than Putin's – the poll which Byelorussian diplomats regard as "viciously provocative" Ц re-surfaced in mass media.

Meanwhile, speculations over a personal mistrust or even envy of Putin towards Lukashenko are groundless enough to be – and are to be, if state-run TV channels a bit reflect the national interests Ц refuted in one simple phrase. This phrase says that the Byelorussian model can be implemented only in Byelorussia. Maybe, also in Peru or Zimbabwe. In Thailand, a relevant attempt already proved a failure. In Ukraine, such an attempt would suggest a bloody civil war.

It is equally true that the illusion of a mechanical transition of the Byelorussian experience across the whole Russia is popular – among a formidable part of the population expecting the state leadership to address its "different issues". This illusion can't be dispelled just by means of propaganda. This task requires decades of conscious effort from the top of the state level, which is already reflected in the priority national projects. If this array of programs starts working, the illusions will naturally fade away. While those illusions are alive, politicians have to admit their existence, and patiently continue to cultivate the grain of optimism on the rough and deserted Russian soil.

In the Russian establishment, this understanding definitely exists. While the Economy Ministry's officials were rising their voice at Belarus' Prime Minister, Boris Gryzlov, the leader of United Russia Party protected Belarus in his negotiations with PACE's president Rene van den Linden. At that time, a curious interviewer from Russia TV was trying to extort at least one disapproving remark vis-à-vis Minsk from Gryzlov's deputy Vladimir Bogomolov – in vain. The United Russia Party is faced with elections of regional legislative bodies. Its members will have to talk to people directly, and to address not only specially prepared but "different issues" as well, the same questions identified in the late XIX century as "damned", or Russian, or "eternal" Ц "Who is to blame?" and "What's to be done?" Can they finally get an answer, or is it still impossible as a century ago?

Number of shows: 1340

ENG

ENG

ENG

ENG